In the first Inside the Mind of an Attacker series, we walked through scenarios of potential attacks on Active Directory, as well as techniques on how to identify and avoid breaches. In this series, we’ll transition to what happens after a successful compromise of Active Directory, in which an attacker attempts to gain persistence after the initial breach. We’ll discuss several different types of persistence techniques, as well as ways of spotting the signs of such persistence. To begin, we’ll start with a quick explanation on why detecting these breaches can be so challenging.

Detecting Active Directory Breaches and Persistence

What makes an Active Directory attack so dangerous? Once breached, the overall availability of your organization to continue functioning may be greatly impacted, slowing or even halting productivity. First, there are the initial effects of a breach, such as a denial-of-service (DOS) attack, which can make Active Directory inaccessible. Next, there is the recovery process—it may be necessary to reset each and every account, or the forest may need to be reconstructed from scratch.

Additionally, there is the potential for persistence. It’s difficult to tell exactly what level of persistence an attacker has already gained in your network. Detecting a breach is often not as easy as one may think. If you’re targeted by skilled attackers, it could be weeks, months, or even years could before your defenses notice that there are attackers living rent-free in your Active Directory forest. Remember, a domain or forest compromise is usually the first step for attackers that are after an organization’s crown jewels. They may gain a token that grants them domain admin rights, for example, by compromising an account granted with domain replication capabilities. From there, they could go dormant for an unspecified period of time, waiting for the best moment to take over your precious database, which contains with sensitive information. They can then steal this data and proceed to sell it on the dark web.

During this period, the signs of breach can be much less overt than domain administrators logging into large groups of computers, malware being indiscriminately deployed to your users' workstations, or even new random domain admin accounts being created. Skilled and goal-focused attackers can carefully evaluate which steps are less detectable, and attempt to execute their tasks in the stealthiest way possible.

Luckily, the perfect crime is rare, as perpetrators typically cannot control every small detail—which means they can leave clues that help to catch them. In order to understand these clues, we must first think like an attacker, learning how persistence is achieved in order to better detect and disrupt these long-term attacks. Let’s walk through a few advanced persistence techniques used by real attackers. Once we’ve understood persistence from an offensive point of view, we can then learn a few of the ways to detect persistence.

Achieving Persistence through Kerberos

Malicious actors often favor the technique of forging Kerberos tickets in a post-exploitation stage. Doing so enables them to access vitals systems within a network, such as an organization’s database containing information of customers or the web application server that is running the code of proprietary applications. In order to better understand attacks that use forged tickets, let's do a quick recap on the Kerberos authentication protocol.

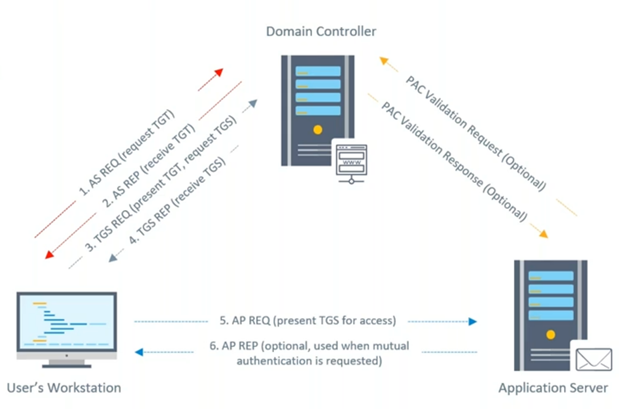

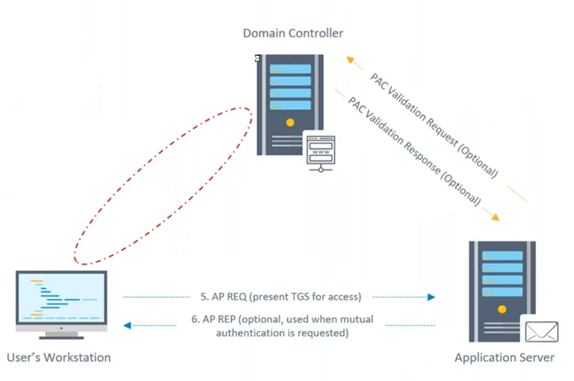

The above graphic illustrates the components of this protocol: First, there is the device that wants to log into a network service, second, we have the device that hosts the requested network service, and lastly we have the Key Distribution Center, which is also the service listening on a domain controller.

Let’s walk through the steps of the authentication protocol:

- As shown with the top red arrow, the device asks the Key Distribution Center (KDC) for a Ticket Granting Ticket (TGT), which is a ticket that allows users to ask for service tickets and presents the credentials of the user account that is requesting the operation. If the credentials are correct, the KDC will emit a TGT that also includes the domain membership information of the initiator account, which is encrypted using the NTLM hash of the KRBTGT account. In theory, this account could be decrypted exclusively by the KDC, as this hash is only present in the domain and the NTLM hash table. The KRBTGT account can be seen as the higher authority in a Kerberos realm.

- The second red arrow shows that the TGT was obtained. The initiator device will send another request to the KDC, which will include the TGT as well as the name of the service that they want to authenticate to. If the TGT is valid and the privileges of the account checks, the KDC will emit a service ticket encrypted with the NTLM hash of the account that runs the requested network service.

- The grey arrows show that the initiator device simply presents the resultant service ticket to the server that hosts a requested service. From there, access is granted.

There are a few small things worth noting about this negotiation that are relevant to forged ticket attacks. First, Kerberos acts as a stateless protocol. This means the KDC does not keep any information on who initiated the Kerberos authentication, when authentication occurred, or which devices have already been issued a valid TGT. So initially, a KDC will blindly trust any TGT encrypted with the hash of the KRBTGT account.

Going one step further, while privileges are being checked, the KDC won't even check its own database. It will once again blindly trust information signed by KRBTGT in the tickets. Attackers who have already compromised the domain have also compromised the NTLM hash of KRBTGT. This means that attackers -using the right set of tools- could forge their own tickets, which your KDC will happily honor.

Golden Tickets

Golden tickets are essentially forged Ticket Granting Tickets, created with tools such as Mimikatz or Impacket. An attacker with power of the KRBTGT password hash will be able to create their own valid TGTs, including the membership of any domain groups that they desire. This typically includes domain or enterprise administrators. This TGT can be directly presented directly to a KDC, entirely avoiding the first step of the authentication phase. By design, nothing will stop the KDC from decrypting the forged ticket, checking permissions, and then emitting a service ticket providing valid access to the desired service. This will occur even if the attacker's domain account shouldn't actually have privileges to access the service.

Golden tickets represent a higher level of stealth. Typically, an attacker that wants to access a particular service post-exploitation will need to resort to noisy techniques, like creating a domain admin account, using an account to edit group memberships, or even logging into the target service with the service account using pass-the-hash. With this technique, an attacker can use their own account or even a fictitious one to request access to particular servers. Of course, this technique does leave its own breadcrumbs that we could use to detect it, but they are much more subtle and difficult to notice. We will discuss these breadcrumbs later on.

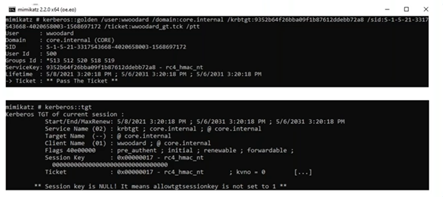

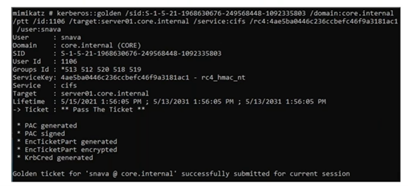

The above screenshots are from the point of view of an attacker creating golden tickets via Mimikatz. An attacker would provide the tool with certain information as arguments, such as the domain name and the Security Identifier (SID). This is all public information for any domain account. They would also be required to pass the KRBTGT password hash, which is only accessible to domain admins.

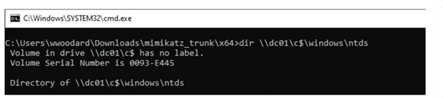

An attacker would also need to add user and membership information. For the user, they could input anything they want, including, as mentioned earlier, a fictitious name. The membership information would automatically be added by Mimikatz to include privilege groups, as we can see in the groups ID field in the above screenshot. However, the attacker also has the option of providing a custom value. In the following screenshot, we can see how the ticket is leveraged after being injected to the current process memory to access the privileged C$ share in a domain controller.

Silver Tickets

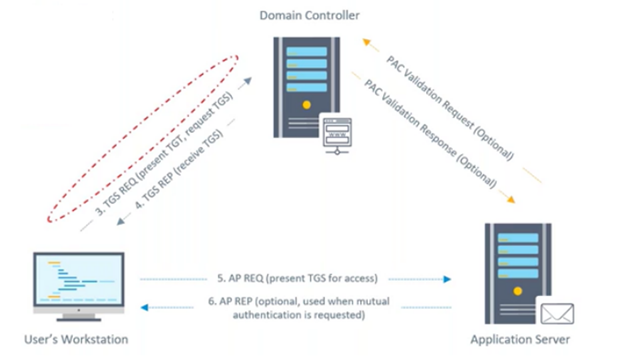

Silver tickets are an even stealthier technique. Skilled attackers pursuing more sophisticated vectors often prefer this variant to golden tickets. Silver tickets are forged service tickets, which means the attacker will only need to dump the NTLM hash of the service owner account instead of KRBTGT, and then they can forge the ticket. Silver tickets can be directly presented to the target server, which allows attackers to avoid the first two steps entirely, as illustrated in the graphic above. Most importantly, this technique helps threat actors avoid the Key Distribution Center.

This attack can be trickier to detect than one using golden tickets, as an organization would need to depend on the event logging capabilities of the target server and the application server. Additionally, it is crucial that somebody is actually watching the logs. A centralized logging solution may be a key factor in detecting attackers that have already compromised Active Directory.

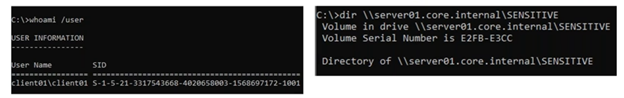

The above screenshots show the creation of a forged silver ticket from the point of view of the attacker using Mimikatz. In this case, the required arguments are similar to those needed for creating golden tickets, but there are a few differences. First, it requires the attacker to include the service principal name of the desired application (in this example, cifs). Additionally, an attacker needs to provide the password hash of the service owner account instead of the hash for KRBTGT. Below, we can see how the ticket is leveraged by a local admin and used to access a sensitive share hosted in server01 through the cifs service.

Detecting Forged Kerberos Tickets

Given the additional stealth these techniques provide, how can we detect the usage of forged Kerberos tickets? In the past, there were some inconsistencies between the fields populated by a real ticket and a forged one. However, if attackers are using up-to-date tools, it is now nearly impossible to tell them apart just by putting two side by side. But there are a few other clues that indicate the presence of forged tickets, including:

Use of Weak Encryption

For golden tickets used to request service tickets, keep an eye out for event 4769, which means a Kerberos service ticket was requested. Usually, forged TGTs are encrypted using the weak RC4 cipher suite. It is possible to detect suspicious operations by looking at the type of ticket encryption for this event, as TGSs will be issued with the same level of encryption as the TGT.

However, depending on your client network configuration, the service ticket encryption level may be elevated before being presented to the KDC, making your operators miss the event, including the weak encryption type.

Correlated Audit Events

Another strategy would be correlating audit events for TGTs and Ticket Granting Services (TGSs). Each TGT presented should be previously correlated to a TGT issuing event for that user. If one cannot be found in the last 20 minutes or so, we might be in presence of a forged golden ticket. For service tickets, keep track of previous service tickets' emission events. Additionally, thoroughly examine the data in the related audit events.

Application Sessions Initiated From Uncommon Sources

Forged service tickets may be detected by looking at the source network address field of event 4624, which means there was a successful login to an account on a member machine. Watch for sessions initiated to particular services from outside the machine, different from the loopback address or uncommon sources. If there is a security identifier different from the name of the service owner, this may be a very good indication that something fishy is going on.

Fake Membership Claims

Group membership information events (event 4627) are also worth looking at. When regular accounts are claiming membership to highly privileged groups such as Domain Admins, this could be a dead giveaway of an attacker attempting to leverage newly gained privilege to impact your business.

Unfortunately, forged golden and silver tickets are not the only way to gain persistence. In part two of the series, we’ll be looking at another persistence technique: Domain Replication Abuse.

Learn More About Active Directory Attacks

Find out how attackers initially breach Active Directory, and strategies on how to prevent it from happening to your organization in our first Getting Inside the Mind of an Attacker series.