Understanding the Evolution of Ransomware

Ransomware, as an active variant of current malware, has undoubtedly undergone a series of changes that have allowed cyber criminals to expand the horizons of clandestine business. In order to try to understand the different "forms" ransomware has presented over time, this article will show the evolutionary line of this latent threat in a compact and concrete way. Ultimately, it aims to demonstrate how ransomware has grown to generate such a high level of complication in organizations around the world.

The number of new variants of ransomware has grown exponentially in recent years, marking an accelerated evolution in both its spread and infection strategies. However, to fully understand the impact that ransomware currently has, it is important to understand how it has evolved over time.

Although some information security companies claim that ransomware attacks began in 2005, there are specific references regarding the use of this type of threat in previous decades.

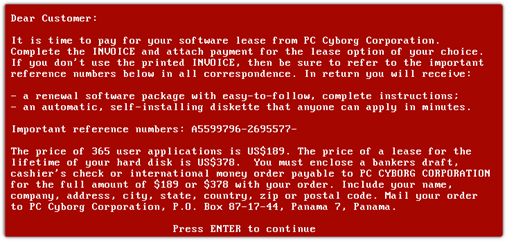

One of the first documented malicious programs using ransomware techniques was the PC Cyborg, which encrypted all the files located on the C:\ drive, making the Windows operating system unusable. It then requested a payment of $189 to be sent to a Panama post office box. The virus was developed by a biologist named Joseph Popp and was discovered in 1989. It was also known as “AIDS” since it was transmitted through floppy disks labeled "Aids Information - Introductory Diskettes," which were sent to subscibers of a World Health Organization AIDS conference mailing list.

The following decade (’90) was not marked by the scourge of ransomware. However, a proof of concept developed by researchers Adam L. Young and Moti Yung, and presented at the IEEE Security & Privacy Conference in May 1996, suggested a type of program that, through the use of public-key encryption algorithms, was able to “extort” money from the owners of infected computers. The research was presented in Cryptovirology: extortion-based security threats and countermeasures and laid the foundations for the well-known and current Ransomware.

Nine years later, there came a turning point with ransomware attack strategies that prevails to this day. In 2005, GPCoder was a notorious ransomware strain due to its encryption technique, a 1024-bit RSA-based encryption algorithm which was considered very robust at the time.

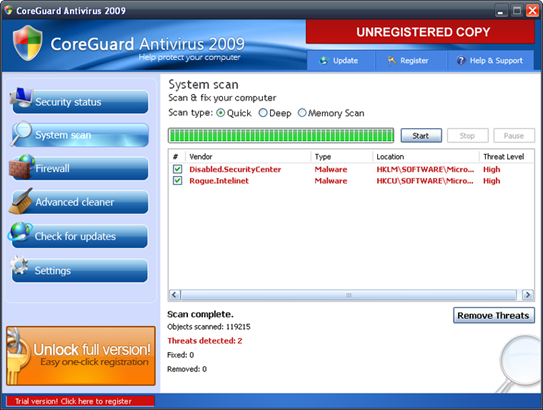

Years later, variants known as FakeAV became equally well known. These malicious programs pretended to be security tools meant to clean potential infected computers, but instead, they did the infecting.

One of the variants with the greatest impact was "Vundo," which used social engineering strategies to steal money from victims by trying to convince them to buy security software such as "CoreGuard Antivirus 2009" that displayed pop-up messages warning about alleged infections. Although it is a less aggressive threat, pop-ups did not disappear until the alleged security program was paid for.

Malicious programs of this style began constantly appearing. Examples such as "WinAntiVirus Pro 2006," "WinAntiSpyware 2007," "AdvancedAntivirus 2008," "MicroAntivirus2009," and "PC AntiSpyware 2010," among many others, were very popular.

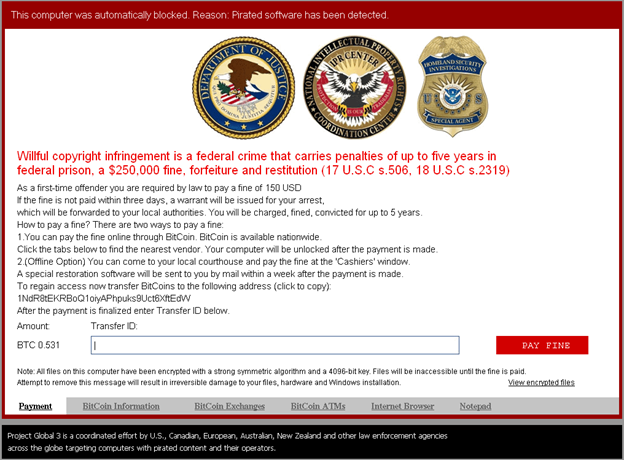

In 2012, ransomware strategies turned in a new direction. Computers infected with a new variant of ransomware blocked the screen through a technique called "Desktop Hijack," displaying an image on the screen with a message from what appeared to be police, FBI, or some other law enforcement agency, alleging that the victim had violated the law by downloading content that violated copyright, such as bootlegged music, or contained something sinister. The message explained that the files on the infected computer were remotely locked by the law enforcement agency, and they would need to pay a fine to the police to regain access to the locked computer.

From that moment on, a massive wave of new ransomware variants threatened the computers of users and organizations, with variants in different languages ensuring global coverage. With such schemes and extended reach, criminal actors or organizations were able to exploit en masse, earning millions of dollars.

In order to make it difficult to trace these threat actors, new infection and data encryption strategies were used. Algorithms based on AES and RSA-2048 bit were transformed into currency, and new variants of ransomware such as "CryptoLocker", "CryptoWall" or "TeslaCrypt", were appearing until the end of 2015.

However, despite the rapid growth we have already covered, ransomware had not reached its peak in the evolutionary process. This occurred in 2016, which included strides like the first ransomware, known as “KeRanger,” to successfully run and infect OSX (Mac computers).

Additionally, numerous reports produced by various security organizations noted that the number of ransomware families increased significantly in 2016.

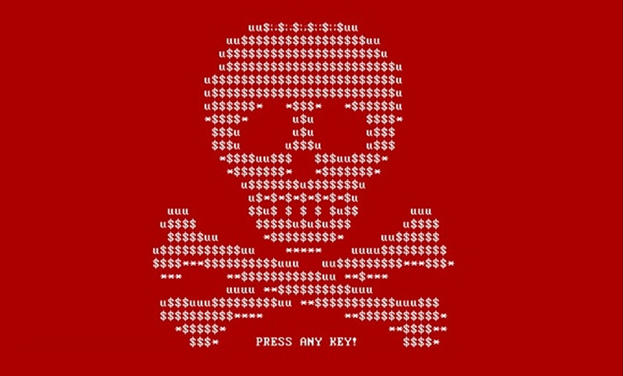

Attack techniques also began to shift, with researchers discovering the spread of a variant that had an infection strategy that implemented a timer which increased the ransom amount as the days progressed. Petya was one such threat that, in addition to using the timer, also exploited the EternalBlue vulnerability in Microsoft Windows operating systems.

With ransomware continuing its rapid growth, 2017 was classified as “the golden year of Ransomware.”

WannaCry spread rapidly throughout the world due to its ability to spread across networks–a feature closely associated with worm type malicious codes–thus quickly accelerating its infection rate. WannaCry's ransom note was translated into 27 languages and its impact generated losses of $4 billion globally.

Since ransomware attacks cost $5 billion in that year alone, the explosive impact that WannaCry had around the world cannot be overstated.

In 2018, the variants that were reported showed more sophisticated infection strategies, including the previously mentioned self-propagation with WannaCry. For example, GandCrab, one of the most popular ransomware strains, and Ryuk were both discovered in late 2018, and managed to affect government entities, hospitals, and universities during 2019.

During March 2019, several municipal departments of the US city of Atlanta, Georgia, were completely paralyzed by attacks from a variant of ransomware known as SamSam (first reported in late 2018), which requested a payment of $51,000 in Bitcoins. The cost estimate of the data loss and recovery exceeded $2.7 million.

As we can see, the sophisticated infection methods continued on the same track in 2019 as in the previous year. The clandestine business model based, RaaS (Ransomware-as-a-Service), facilitated the extension of numerous variants that, while appearing under different names, were technically very similar. In addition to being more sophisticated, ransomware became more targeted, being disseminated to attack specific entities, mainly large companies.

Variants of Zeppelin and REvil are good examples of this strategy. Zeppelin was discovered later that year and used to attack large companies in Europe and the United States. At the end of 2019 REVil threatened to sell or make public the sensitive data stolen from the computers of different companies’ victims if the ransom went unpaid.

Clearly, many variants of ransomware discovered years ago are still active today. However, in early 2020 we experienced a new and much more aggressive type of non-computer virus known as COVID-19 or coronavirus that ultimately exploded into a full blown pandemic.

As in any global event with widespread media coverage, malicious actors took advantage of this circumstance and began to spread computer threats through social engineering, exploiting the crisis and its surrounding panic. Unfortunately, ransomware was no exception.

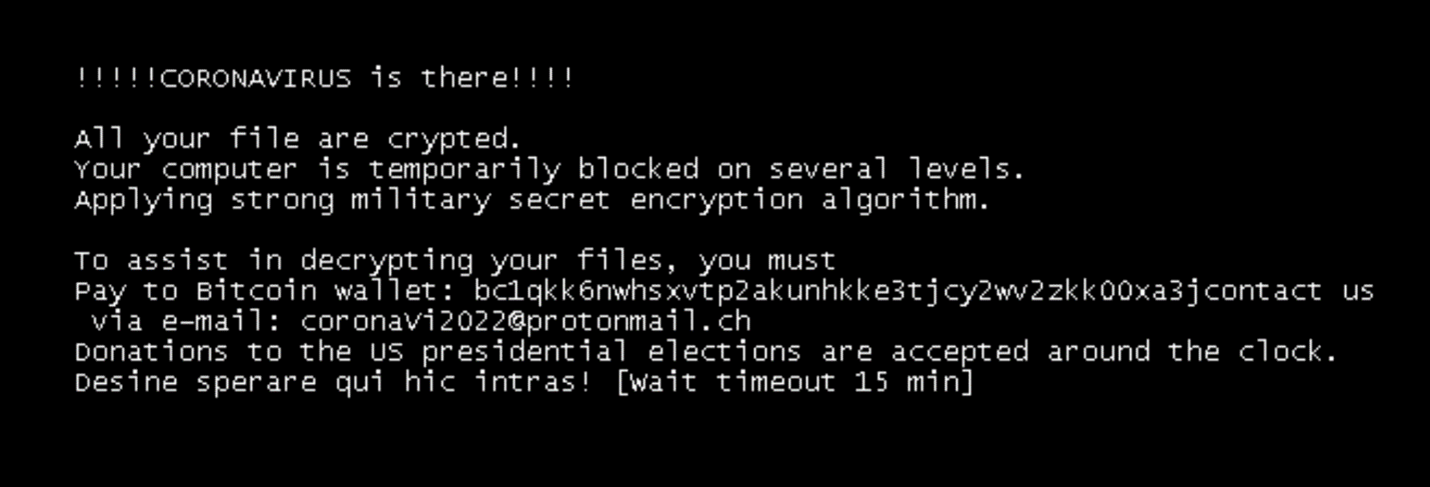

The CYREN company, through its business unit F-Prot antivirus, named a recently released variant of ransomware as a “Korownai.A,” that many researchers are generically calling “Ransom.CoronaVirus."

This variant exploits the pandemic by sending a message that begins with the sentence "!!!!CORONAVIRUS is there!!!!" and then changes the name of the C drive.

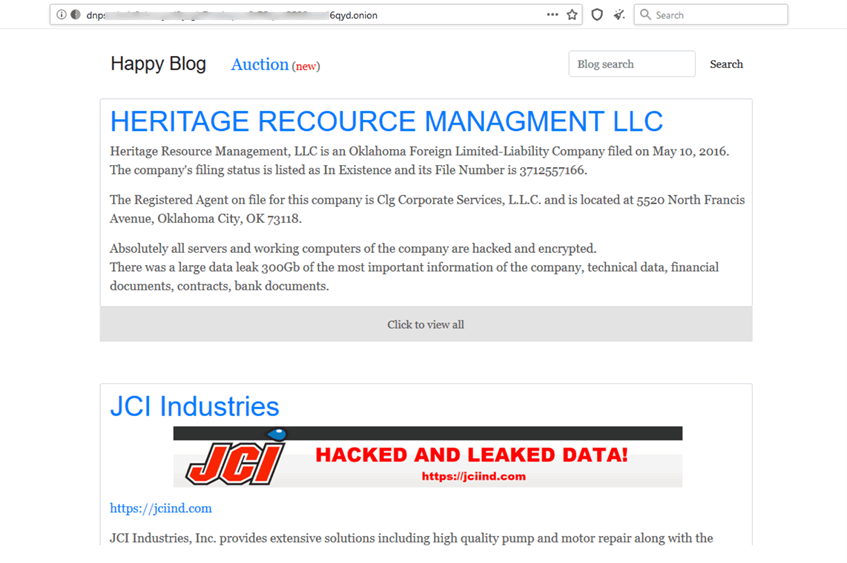

Additionally, the evolution in ransomware fraud strategies continues. Instead of merely encrypting or destroying data, there is a new focus on publishing classified, sensitive data from corporations around the world. This new methodology is installed in practically all modern ransomware families.

Attacks extort victims by threatening to go public with sensitive information that was stolen through the infection chain. This information is typically published on the dark web, providing access to other malicious users. It’s typically only used in cases where the initial ransom was not paid by the victims.

For example, the ransomware strain REvil (also known as Sodinokibi) publishes the stolen information on a resource called “Happy Blog,” which is available, as mentioned above, through the dark web.

Finally, ransom payments have rapidly escalated. 2020 saw the highest ransom demand yet reported—a staggering $30 million, which was double the amount of the previous record. The average ransom paid skyrocketed from $115,123 in 2019 to $312,493 in 2020. At this pace, ransomware may soon become a billion dollar industry.

Ransomware shows no signs of slowing, and will more than likely continue to evolve because its exploitation has become one of the largest and most lucrative fraudulent businesses in the world. Because of its profitability, those behind the development of ransomware, as well as its promotion and sale, have become vital players in this business chain.

Ransomware’s level of "aggressiveness" is so dynamic and volatile that an attack and subsequent recovery can cripple businesses both temporarily and permanently. Therefore, it is of paramount importance to promote prevention mechanisms aimed at mitigating the complex consequences of ransomware.

Safeguard your organization against ransomware

Learn how to reduce your risk against ransomware attacks in our webinar, How to Manage Ransomware Attacks Against Your Remote Workforce.